Popular topics

-

References

Blaine DP (1810). A domestic treatise on the diseases of horses and dogs. Londen T Boosey.

Decker B et al. (2015). Comparison against 186 canid whole genome sequences reveals survival strategies of an ancient clonally transmissible canine tumor. Genome Res 25, 1646-1655.

Murchison EP et al. (2014). Transmissible dog cancer genome reveals the origin and history of an ancient cell lineage. Science 343, 437-440.

Murchison EP (2008). Clonally transmissible cancers in dogs and Tasmanian devils. Oncogene 27, S19-S30.

Murgia C et al. (2006). Clonal origin and evolution of a transmissible cancer. Cell 126, 477-487.

Nowinsky M (1876). Zur Frage ueber die Impfung der krebsigen Geschwuelste. Zentralbl Med Wissensch 14, 790-791.

Ostrander EA et al. (2016). Transmissible tumors: Breaking the cancer paradigm. Trends Genet 32, 1-15.

Strakova A and Leathlobhair MN et al. (2016). Mitochondrial genetic diversity, selection and recombination in a canine transmissible cancer. eLife 5, e14552.

The oldest known naturally occurring cancer is transmitted between dogs

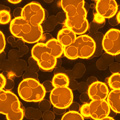

Over 11,000 years ago, a relatively inbred canine resembling a malamute developed a cancer now known as canine transmissible venereal tumor (CTVT) or Sticker’s sarcoma. Usually, when a cancer bearing animal or human dies, the existing cancer dies with them; however, CTVT has long outlived the existence of the dog from which it originated.

What is CTVT?

CTVT can be considered a sexually transmitted disease since cancer cells can be transferred between dogs during mating. Accordingly, it has spread across the world over the years and is currently endemic in at least 90 countries across all continents. It is speculated that over the past 200 years, the cancer spread through the transport of dogs on ships along historic trade routes (Strakova and Leathlobhair et al. 2016). It may have reached the Americas within the last 500 years, possibly introduced by the dogs of travelling Europeans (Strakova and Leathlobhair et al. 2016). CTVT is therefore the oldest known naturally occurring cancer (Murgia et al. 2006, Murchison et al. 2014).

The first report of CTVT in the scientific literature is from London in 1810, where the disease was noted as one of only two cancers known to afflict dogs (Blaine 1810). Since that time, several studies have been published describing the genomic and molecular traits of the cancer. The transmissible phenotype of CTVT was first documented in 1876 by Nowinsky, who defined it as a histiocytic tumor (Nowinsky 1876, Ostrander et al. 2016). In 2014, Prof. Elizabeth Murchison and colleagues at the University of Cambridge demonstrated that CTVT contains 1.9 million mutations, which is far greater than the number of mutations in human cancers (approximately 1000-5000 mutations) (Murchison et al. 2014). Mutations in major known cancer genes such as CDKN2A, MYC, and ERG were shown to be characteristic and necessary for CTVT survival (Murchison et al. 2014). Recently, the same research group demonstrated that dogs with CTVT contain mixed mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) (Strakova and Leathlobhair et al. 2016). They show that mtDNA from the normal cells of the host migrate into the tumor and fuse with the tumors own mtDNA in a process known as recombination. This is the first time this process has been observed in cancers of any kind, and the researchers point out that it has occurred at least five times since the original CTVT arose. It is possible that this process of “stealing” mtDNA from the host helps the tumor to survive.

CTVT escapes immune detection

Other studies have shown that CTVT has a complex immunological profile that allows the tumor to escape immune detection by the hosts. It has been shown that of the 1.9 million mutations in CTVT, a significant number of mutations were present in molecular pathways that function in immune surveillance (Decker et al. 2015). Mutations were also observed in initiator and executioner proteins of apoptosis (programmed cell death). These mutations ensure that the tumor avoids destruction by the immune system and evades cell death mechanisms, thus continuing to survive. Interestingly, spontaneous regression of CTVT has been observed in some dogs (Murchison 2008). Dogs that have recovered from CTVT demonstrate serum-transferable immunity to re-infection. Studies show that the transition to the regressive phase of CTVT is accompanied by a marked increase in immune cell infiltration into the tumor site (Murchison 2008). The detailed mechanism by which some dogs overcome CTVT and survive is poorly understood and is currently being investigated.

A naturally transmissible cancer

CTVT represents a biological curiosity of significant magnitude, and scientists are actively investigating how the tumor originated. CTVT is one of three naturally occurring cancers known to be clonally transmissible in mammals. Devil facial tumor disease, which afflicts Tasmanian devils (Sarcophilus harrisii) and a lymphoma that affects Syrian Hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) are the other known transmissible cancers in mammals. The occurrence of transmissible cancer is a rare event and understanding how they originate will aid in determining whether such additional cancers are likely and in what types of species.

Bio-Rad has a range of canine antibodies

To support veterinary scientists in their quest to understand complex diseases that afflict canines, such as CTVT, Bio-Rad offers a range of monoclonal antibodies and recombinant proteins for studying immune responses in dogs. Find your canine antibody here.

References

Blaine DP (1810). A domestic treatise on the diseases of horses and dogs. Londen T Boosey.

Decker B et al. (2015). Comparison against 186 canid whole genome sequences reveals survival strategies of an ancient clonally transmissible canine tumor. Genome Res 25, 1646-1655.

Murchison EP et al. (2014). Transmissible dog cancer genome reveals the origin and history of an ancient cell lineage. Science 343, 437-440.

Murchison EP (2008). Clonally transmissible cancers in dogs and Tasmanian devils. Oncogene 27, S19-S30.

Murgia C et al. (2006). Clonal origin and evolution of a transmissible cancer. Cell 126, 477-487.

Nowinsky M (1876). Zur Frage ueber die Impfung der krebsigen Geschwuelste. Zentralbl Med Wissensch 14, 790-791.

Ostrander EA et al. (2016). Transmissible tumors: Breaking the cancer paradigm. Trends Genet 32, 1-15.

Strakova A and Leathlobhair MN et al. (2016). Mitochondrial genetic diversity, selection and recombination in a canine transmissible cancer. eLife 5, e14552.

You may also be interested in...

View more Veterinary or Feature blogs